Forgotten Kings & Bloody Truths

: Unearthing REAL Beowulf

Every legend has a secret, and Beowulf is no exception. For centuries, we've been spun a yarn about myth and monsters, but the real story, the one etched in blood and ancient dust, is about to be unearthed. Prepare to see the Anglo-Saxon world like never before.

Alright, let's cut through the academic fog that often hangs heavy around Beowulf. You think it's all about some hairy-arsed hero ripping off monster limbs, right? Well, yeah, some of it is. But dig a bit deeper, and you pull up some proper historical grit, especially when you start looking at the Geats and their kings.

For centuries, scholars have been wrestling with Beowulf, trying to figure out if it’s a bit of made-up fancy or if there's real history woven into its lines. Turns out, there’s a hell of a lot more truth than fiction, especially when you shine a light on the Geats.

The Geats: Not Just Footnotes in a Saga

First off, these "Geatas" aren't some imaginary tribe from a fantasy elegiac poem. We're talking the Götars, from what's now Sweden. The old tongues, Old English and Old Norse, line up perfectly. The names, the sounds – it all clicks into place like a well-oiled lock. These aren't just academic musings; these are actual linguistic facts.

Now, here's where it gets interesting. There’s a solid bit of evidence that these Geats actually got stuck in, violently, outside Scandinavia. We're talking about a raid on Frisia – that's today's Zuyder Zee – sometime between 510 and 530 AD. And who's leading the charge? None other than Hygelac, Beowulf’s very own king in the poem.

Think about that for a second. We've got Gregory of Tours, a bloke born a couple of decades after the fact, writing about this raid. And then, completely disconnected, we’ve got the Beowulf poet chiming in with the same story. That’s not a coincidence, mate. That’s a history echo. Hygelac, overwhelmed on a beach, trying to get his gold onto some ships, was swallowed by the Franks. His "giant bones" are supposedly buried on an island near the mouth of the Rhine. If that doesn't put a shiver down your spine, you've got no history in your blood.

Historical Heavyweights: Ongentheow and His Brood

While Hygelac's father, Hrethel, and his brothers, Herebeald and Haethcyn, are a bit thin on the ground historically, the identification of Hygelac with "Chochilaicus" (that's Gregory of Tours’ version) is a massive bloody deal. It’s like finding the Rosetta Stone for early medieval history.

There is a widely accepted academic consensus that Hygelac, the Geatish king mentioned in Beowulf, is indeed the same historical figure as "Chochilaicus" (or Chlochilaichus/Chochelagus), the Danish king mentioned by Gregory of Tours in his History of the Franks.

Here's why it's considered a verified identification:

Phonetic Similarity: The names Hygelac and Chochilaicus are phonetically very close, especially considering the Anglicisation and Latinization of names over time.

Contextual Overlap: Both figures are described as Scandinavian kings who led a naval raid into Frisia (modern-day Netherlands/Germany) and were killed during the expedition.

Chronological Consistency: The dating of Hygelac's raid in Beowulf aligns with the historical accounts of Chochilaicus's raid, which is generally placed around 520-530 AD.

External Corroboration: Besides Gregory of Tours, other historical sources like the Liber Monstrorum and the Gesta Danorum also refer to a similar historical event involving a Scandinavian king and a raid into Firsia, further substantiating the claim.

In brief, the identification is considered highly probable and widely accepted within the fields of Anglo-Saxon studies and early medieval history.

And it doesn't stop there. Take Ongentheow, for instance. He’s in Widsith – another ancient poem – alongside a bunch of other historical figures. So, yeah, it's a pretty safe bet that the Ongentheow in Beowulf is the real deal. And his sons? Onela and Ohthere? They're popping up in the Ynglinga Saga and Ynglinga Tal, which are Scandinavian sources. The dates align, too: early 6th century.

This isn’t just some dusty academic argument. This is putting Beowulf right smack dab in the middle of a verifiable historical period. All that bollocks about Beowulf being about a Mercian king from the 9th century? Forget it. Why would East Anglians be writing epic poems about Mercian kings when they were constantly at each other's throats? It just doesn't stack up, does it?

Mercian Kings from 823 to 829:

Beornwulf 823-826.

Ludeca 826-827.

Wiglaf (1st reign) 827-829.

Most scholars, the ones with their heads screwed on, reckon Beowulf was probably penned in the early 6th century. And when you look at the evidence, bloody hell, it’s hard to argue otherwise.

Shifting Sands and Beowulf's Shadowy Past

Now, what about our titular hero? Beowulf himself. The poem tells us he helps Eadgils avenge himself against Onela, aiding him with "weapons and warriors over the wide sea." And guess what? Scandinavian sources back this up. The battle between Eadgils and Onela happened on the ice of Lake Wener. Real battles, real frozen lake, real cold-blooded history.

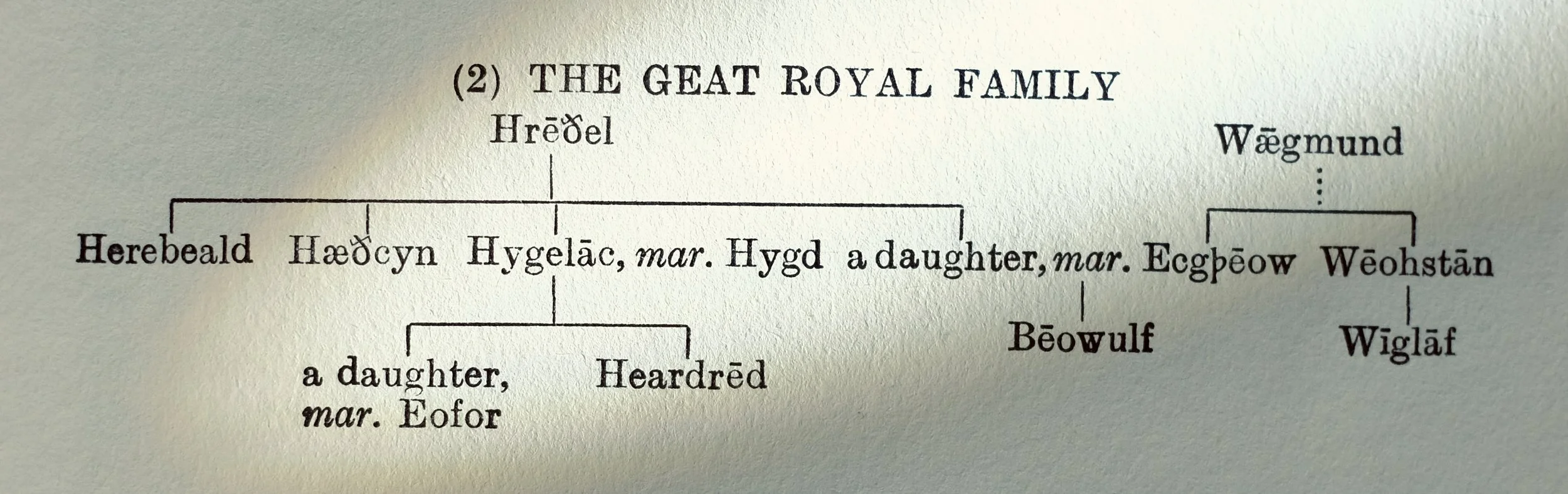

But here’s the kicker, the bit that’ll make you scratch your head. There’s no mention of Beowulf as a Geatish king anywhere else. None. And his name doesn't even fit the alliterative naming conventions of the royal houses. Seriously, look at this:

Hrethel - Herebeald, Haethcyn, Hygelac, Hygd. (See the 'H'?)

Waegmund - Weohstan - Wiglaf. (All 'W'.)

The point of this is so father and son can be named in song together.

Now Beowulf? He’s put down as the son of Ecgtheow, linked to Wæægmund. That's a 'W', then an 'E', then a 'B'. It's a dog's dinner of a family tree, linguistically speaking. It doesn’t scan. It doesn't fit. And without some imaginative kennings, their names won't fit within an alliterative verse of poems and songs.

So, if Beowulf was such a legend, reigning for fifty years (with no heirs by the way), the last great Geatish king, why is his name lost to every other record? The brutal truth is, the bloke's probably a poetic construct, a fantastic figure. His feats, ripping off Grendel's arm and all that, they're not provable. But the setting, the background of his story – that's undeniably steeped in actual historical events. Even his deeds, like killing Grendel and his other, could be attributed to 'The Bear’s Son', 'The Saga of Grettir', and others, which we'll get to later on.

This poem isn't just a fantasy. It's a gritty lens into the late 5th and early 6th centuries, a time of warring tribes, kings, and bloody, hard-won battles. Beowulf might be fictional, but the world he walks through, the sweat and the blood of the Geats, that’s as real as it gets. And that, my friends, makes it a damn sight more interesting than a simple monster story.

This journey into Beowulf's hidden history isn't just academic; it's a stark reminder that even our wildest tales are often anchored to the hard, unyielding bedrock of human experience. The monsters might be fiction, but the heart of battle, the loyalty of kinsmen, the fight for survival – that, my friends, was brutally, undeniably real.

From R. W. Chambers book, Beowulf: An Introduction to the Study of the Poem.

Event Portfolio

Street Portfolio